This poem was a response to a writing-exercise prompt for my writing group. My original plan was to submit to literary journals with hopes of publishing. I haven’t done that sort of thing in many, many years and would like to start again. The poem is good enough, I think, and on the day I shared it with my writing group, they were helping me brainstorm a list of places to send it.

So that was my original goal: to have this poem accepted somewhere and get the publication credit.

But then I thought about my photos.

Our writing group is meeting via Zoom right now because one of our members is in Florida. When I read this poem aloud to my group, they liked it well enough. But I was also sharing the document on my screen as I read aloud, and when I eventually scrolled down past the last line of the poem and got to the attached pictures on the next page, then they really liked it. Like, the photos kind of make the poem. While the language itself is evocative, you really need the images to experience the poem in full.

So although I’ve dithered quite a bit in the last two weeks about whether or not to try for publication in a lit mag, as I’d love to see this published in a legit space, I have trouble imagining who would take it and publish several of my photographs alongside it.

In the end, I wound up coming back here to my own tiny little corner of the internet, where I can have “artistic freedom” (a.k.a. complete control 🙂 ) and can see my poem published in the exact format I want it to be presented in.

So first, here’s my poem. Photos and explanation to follow. (By the way, I’m inserting my poem as an image because I don’t like the way WordPress formats poetry.)

[UPDATE – I just looked at this post on my phone, and while the image text shows up great on my laptop, on my phone I had to click on the “image” to see the print clearly. FYI, in case you’re on your phone and the poem looks blurry. All you have to do is click on it!]

And now here are the photographs.

Except maybe I should back up a little bit first, though. The writing group exercise for the week I wrote the poem was: “Write something in response to a painting” (worded better than that, but that’s the gist of it).

However, I couldn’t find any paintings that spoke to me. I mean, obviously they spoke to me in the way that art does, but they didn’t speak to me in terms of inspiring me to write something of my own in response. So I turned my attention from paintings to photography, thinking maybe I could find a famous photo that could spark something. Or maybe, if photography didn’t pan out, a sculpture could work.

And then, out of the blue, I remembered some photos I took of a sculpture.

In summer 2019, a fellow professor and I led several Milwaukee School of Engineering students on an “art walk” along Milwaukee’s Riverwalk to view the sculptures both there and along Wisconsin Avenue. (Aside: Milwaukee has a surprising amount of public art. And further aside: You can read about our “art walk” experience HERE.)

One of the sculptures we saw on our walk that day absolutely haunted me. So much so that I went back another day and took lots of photos from all different angles and distances.

As soon as I made that loose connection between photography and sculpture for my writing group exercise, I remembered photographing that particular sculpture and knew instantly what I would write. Not that the poem sprang fully formed from my forehead like Athena from Zeus, but I did have an immediate “flash” of what I wanted to say in its entirety. That is, I kind of saw the poem as a whole from the very start, albeit in a pretty vague, inchoate kind of way. It was a “feeling” that had shape, if that makes sense.

I wanted lots of mournful, haunting words, for example. And I wanted the figures to speak in some way, even if nothing more than to offer silent testimony on ideas like the emptiness of the void, the omnipresence of evil (the type so banal that we don’t even see it), and the callousness of our ignorance. The figures in this sculpture are absolutely horrifying up close. Yet the sculpture sort of fades into the woodwork (so to speak) of its busy surroundings, in a spot seemingly “tucked away” in a nook next to one of the four bridge house pillars on Kilbourn Avenue, a major east-west downtown street that hundreds, if not thousands, of people drive and walk past every day. Maybe that adds to the horror, the fact that it occurs in such an unobtrusive way in such a high-traffic setting.

In addition to “haunting” words, I wanted my poem to have a “kaleidoscopic” feel that would mimic the experience of needing to walk all around the figures (which are different heights and are facing in different directions), standing alternately far away and then coming in close again, to view everything there is to see and to take in the sculpture as a whole. Plus, I liked the paradoxes embodied in this sculpture: sightless eyes, silent screams, missing arms and legs, and “prosthetic” arms and legs resembling crutches or braces for use with limbs that aren’t missing as these are. I liked the paradoxes, mind you, not the actual horror of sightless eyes and silent screams. Just so many details and perspectives happening all at once as you experience this artwork, which to me seems very kaleidoscopic. Always changing, always shifting perspectives.

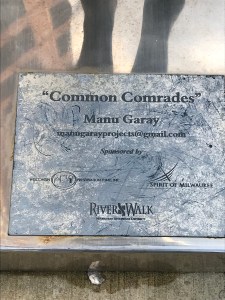

So anyway, were this poem to be published, I knew I really wanted the pictures I took of “Common Comrades” to run alongside so that anyone reading could feel this sculpture as a “whole” experience the way I did. And because I couldn’t imagine any lit mag giving over the amount of space I thought these images needed, I decided to publish it all myself.

FYI, the red and white candy-striped apparatus in the background below is the arm that lowers to stop foot and vehicular traffic when the drawbridge rises to accommodate boat traffic on the Milwaukee River below.

The official description of “Common Comrades” on the Milwaukee Riverwalk’s website reads: “These works, abstract versions of the female form, are inspired by the environment around us.”

Which . . . what?

To me these figures are specters of war, a chilling testimony . . .

[Aside: It’s really hard for me to use the word “testimony” in my own writing now that AI-generated texts have kind of ruined it via ubiquitous assertions that anything it’s writing about is a “testimony” to whatever. I resent that appropriation and cheapening of the word, LOL]

. . . to the millions of people killed in the convulsive horrors of the mid-twentieth-century’s ideological self-righteousness—in Germany, in the Soviet Union, in the Balkans and the Middle East. I’m sure I’ve accidentally omitted a few areas of ethnic cleansing in there, but you get my drift. The twentieth century will surely go down as the bloodiest, most murderous period in human history. (I hope, anyway. God forbid we should see worse times ahead.) The title “Common Comrades” makes me think that the figures represent all the ordinary people caught up in forces of war beyond their control, mere pawns in the stratagems of the powerful, and trapped in maelstroms of hate so all-consuming as to transcend reality almost to the level of abstraction.

Of course, my interpretation is my interpretation. Your mileage may vary. I also don’t know where that description’s language originated. With the artist? And if so, is that description intentionally vague and open ended?

One comment I saw attached to a Flickr (styled “flickr” on their website, with a lowercase “f”) photo said:

Described as conveying “…the message of inclusion for the poor, oppressed, and outcast.”

Unveiled on Milwaukee’s Riverwalk September 6, 2010.

Does it mean something that I went straight to war and ethnic cleansing in my interpretation instead of thinking of female form abstractions inspired by the context of our surrounding environment?

That gives me something to think about, truly, because why should one type of violence have come to mind more readily than others? Why did I not think about domestic violence first thing, for example? Or random street violence? What made me visualize massive violence at scale rather than small, separate incidents of violence inflicted against individuals?

And I totally did not see this sculpture as being a message of “inclusion.” Definitely the part about the poor, oppressed, and outcast, but more about the great wrongs being done to them than about a call to be inclusive. That is, I see “Common Comrades” as art that calls out crimes against humanity, and “inclusion” sounds like way too tame a response for the immense evil at work here.

Again, your mileage may vary 😀

I don’t know anything about the artist, Manu Garay. Text accompanying a flickr photograph of the sculpture mentions him as a “local artist.” I did find someone on LinkedIn named Manu Garay, based in Milwaukee, so that person may be him. His education is listed as MIAD, which is the Milwaukee Institute of Art and Design, an additional “clue” that logically seems to point toward this LinkedIn person being the creator of Common Comrades. The LinkedIn profile also lists a “freelance design” website URL, but when I clicked through, I got a “this site can’t be reached” message.

Which, if this LinkedIn Manu Garay is the Manu Garay, makes me sad. The artist who created this sculpture is amazingly talented and ought to have an online presence. But I couldn’t find anything. Maybe he’s retired or has stepped away from doing art projects.

There is that Gmail address listed on the sculpture plaque, however. Doesn’t that make you think the artist might welcome hearing from people? So I’ll try contacting him that way and send my photos and a copy of the poem. He might not care for my interpretation, but even so, if he’s anything like me, he might also be happy knowing that his work affected someone so viscerally that it created a new work of art via the energy transfer of sympathetic vibration.

Pingback: A tour of public sculpture along Milwaukee’s Riverwalk and Wisconsin Avenue | Katherine Wikoff

Pingback: “The Art of Forgetting” – A short story, plus my start-to-finish ChatGPT creative conversation | Katherine Wikoff