This week’s short-short story, “The Art of Forgetting,” was fun to write.

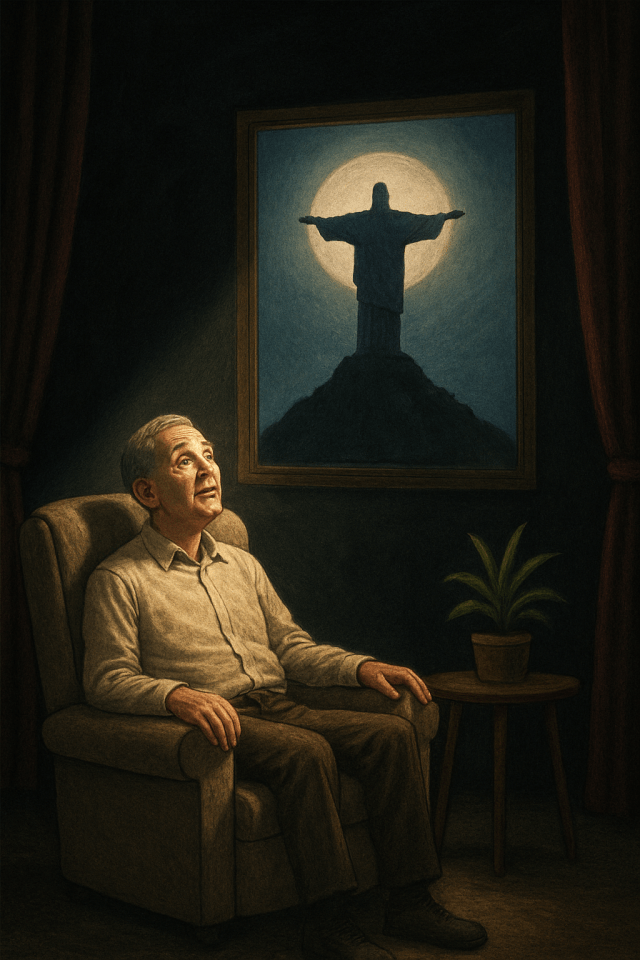

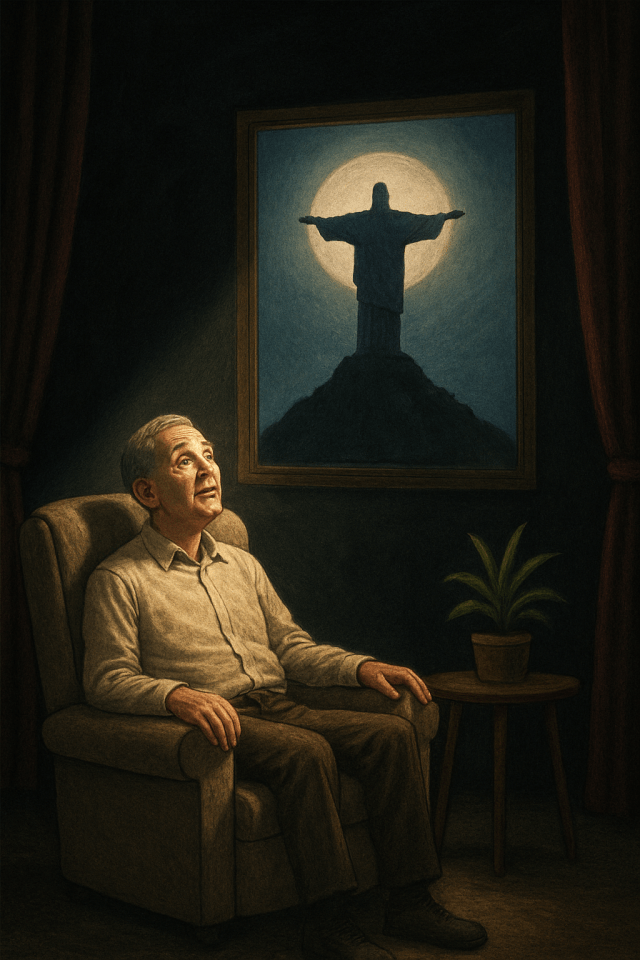

‘The Art of Forgetting’ – ChatGPT Image, prompted by Katherine Wikoff, Aug 19, 2025, 01_38_14 PM

Before I go any further, here are the relevant PDFs for this week’s post.

First, HERE is the PDF of my short story, “The Art of Forgetting.”

And HERE is my entire ChatGPT creative conversation. It’s long and meandering, but it may have some value if you’re interested in seeing how I wrote the story, at least the “trail” left behind by my “chat.”

Finally, HERE is chat I used in prompting ChatGPT to create the image that illustrates this post.

Like many of my short pieces, this short story began as a writing group exercise. The prompt derived from a line in “The Blind Pig” (‘The Blind Pig’ – A short story by Katherine Wikoff, with ChatGPT assists), the first short story I finished with ChatGPT. The specific line was this:

“quietly rotting memories”

My friend Karen had highlighted it as a phrase she especially liked during her critique of that story, so we decided to turn it around and build on it as the prompt for our next meeting’s exercise. It became the seed for my story’s main character, Edgar, and his frightening journey through grief.

If you look at the “Appendix Chat” I used to prompt this week’s story, you’ll see that ChatGPT suggested a number of story ideas based on the phrase “quietly rotting memories.” Almost none appealed to me—but something about the following description caught my eye and sparked my imagination:

“An elderly man pretends to have dementia to avoid his family, but his lies accidentally trigger real past events. Now he has to untangle his quietly rotting memories from the fake ones he invented.”

That logline emerged only after a lot of back-and-forth with ChatGPT. I asked for multiple lists of potential ideas, identified a few I liked, requested more, and gradually whittled them down—rinse and repeat—until the premise and character finally felt right. I remember feeling a little guilty about being “wishy-washy,” like I was wasting ChatGPT’s time by not settling on a direction. But that’s exactly one of the gifts of working with AI: you can keep iterating until something clicks. After rejecting plenty of false starts, I landed on a premise that truly spoke to me—and that made the project so much more fun.

Much of the initial drafting I don’t remember (it was two months ago), but I do recall realizing early on that this story could lean toward dark comedy. The subject matter (dementia) is scary and upsetting, and I could easily see myself slipping into pathos and melodrama, so the idea of approaching it with an edgy wit appealed to me. Plus, ChatGPT helped nudge me in that direction by suggesting Edgar’s family escalate his ruse by sending him to Shady Pines and tossing out his jazz collection. Those tiny details instantly gave me a sense of Edgar—his history, his quirks, the kind of man who’d cling to his records. Once the theater background started to surface, I embraced it as a source for motifs and perspectives.

In my last “Creative Practice” post, I mentioned that I had noticed my photography “style” emerge gradually over time, almost as a byproduct of taking photo after photo. The same seems to be happening in my writing with ChatGPT. Even though I’ve only produced a handful of pieces, the speed at which I can now write—much faster than I could without AI—has already revealed recurring rhythms and themes in my work. These might be the beginnings of a literary “voice.” I expect this will become even clearer in a couple of weeks, when I share my next original piece, a poem I’ve already finished called “The Museum of Mislaid Days.”

One thing I’ve begun to notice about my style is that I’m oddly drawn to morbid subject matter—by which I mean things that feel nostalgic, tragic, or unsettling—and to liminal spaces. I’ve sensed this in my photography, although there it manifests more in abstraction, geometry, detachment, and abandonment rather than “morbid” content. It’s a surprising realization (although, why?) to see these patterns emerging in my writing as well.

For example, I wrote a poem for a writing group exercise this past winter, “Common Comrades,” about a sculpture along the Milwaukee Riverwalk. I didn’t invent the horrifying subject matter—it was right there in front of me on Kilbourn Avenue at the river—but still it was that sculpture that spoke to me, not one of the many others installed along the Riverwalk. To put it in terms of the “intertextuality” I talked about in my last “Creative Practice” post, my poem entered into a dialogue with the “Common Comrades” sculpture. Both sculpture and poem now speak to each other, and the result is beautiful to me precisely because it is so sad and unsettling.

Edgar’s story for this week nearly went the same way. In draft after draft, he ended up completely lost to madness.

But then, just a few days ago, I asked myself: Why? Why does he need to be lost? My work so often seems to end on a “down” note—but it doesn’t have to. I could let Edgar find something lighter, even if somewhat ambiguous, at the end. So I did. Judge for yourself whether it works, but for me, giving Edgar a measure of hope felt right.

That, to me, is one of the fascinating things about creative practice—patterns emerge, sometimes in spite of ourselves. I don’t know what they “mean.” I’m not interested in psychoanalyzing it. What I do know is that creativity often feels like something flowing through me rather than from me.

When I’m walking down the street and something suddenly strikes me as a potential photograph, I don’t know where that impulse/recognition comes from. I don’t plan for it. That moment really does feel like the muse is announcing its presence. The same thing happens in writing. Even with my novel, where I’ve made deliberate choices about subject matter, once I begin drafting, characters and plot twists pop up and surprise me. It’s as if the stories are already out there, waiting, and my role—sometimes with AI’s help—is to act as the channel that brings them into shareable form.

This Week’s Suggested Creative Practice

Getting Acquainted with the Artist Your Creations Knew Before You Did

Each week in this (nascent) “Creative Practice in the Age of AI” series, I offer a short list of “creative invitations”—small exercises that I hope can be meaningfully adapted to your own work. This week’s invitations focus on self-discovery: not only noticing the recurring styles, subjects, and images that surface in your creative practice but also reflecting on what they reveal about the artist you are becoming.

1. Trace Your Echoes – Pull out 3-5 recent works you’ve made (a photo, a paragraph, a sketch, a song draft). Jot down what imagery, tone, or subject matter repeats across them. What patterns surprise you? Which ones feel inevitable?

2. The Morbid–Tender Sway – Write (or sketch/photograph) something in your usual style. Then rewrite/reframe it with the opposite emotional register. If you lean “dark,” give it a lighter, gentler ending (like Edgar’s) or add a comedic twist. If you lean “light,” twist it toward the uncanny or imbue it with tragedy, sadness, or despair.

3. Memory Remix – Take a phrase or fragment from an older work—something that still resonates with you—and use it as a seed for a new piece. (Like what my writing group did with “quietly rotting memories.”) Notice how the original context colors the new one.

4. AI as Trickster – Ask ChatGPT (or another AI) to generate five versions of a story premise, poem opening, or image idea based on one phrase you like. Circle the least appealing one and try making something from it anyway. (Constraints sometimes reveal surprising aspects of your style.)

5. Your Liminal Self-Portrait – Create a short piece (poem, photo, drawing, even a journal entry) set in a “threshold” space—an airport lounge, a waiting room, a hallway. Then look at what kind of mood your work naturally drifts toward: anxious, whimsical, mournful, playful?

(Note: In addition to the denotative definition of “liminal” spaces as “transitional,” “threshold” spaces between one “state” and another, like that dreamy threshold between wakefulness and sleep, I am also interested in the connotative definition of “liminal” spaces as empty places intended to be occupied, except no one is there, and which when you experience, view, or read about them, you feel a sense of uneasiness. There is often something eerie or mournful or vaguely threatening about a “liminal” space.)

Thanks so much for joining me this week! I hope you enjoy “The Art of Forgetting” and the behind-the-scenes peek at its creation.