Inspiration may strike, but creativity accumulates. One is lightning in a bottle; the other is molasses—slow to pour, but sticky enough to catch the stray ephemera that lend rich flavor to whatever artistic projects you’ve got baking.

Creativity is not a trait you’re born with so much as it is a practice you build and a dialogue with everything that came before.

A creative life isn’t built on rare moments of brilliance but, instead, on repetition: showing up and making something out of nothing, again and again. It’s taking 200 photos to keep three. Writing five pages to find one good paragraph. Baking six test batches before the recipe finally tastes the way you imagined. Learning to love the part where it doesn’t work—yet.

That kind of effort might not be glamorous, but over time, it yields something miraculous: a voice, a vision, a style that’s unmistakably your own.

That’s what happened to me with photography. Over the past fifteen years, I’ve taken thousands of photos—mostly unplanned, usually because something caught my eye. I wasn’t trying to develop a personal “style,” but to my surprise, one emerged anyway. People began pointing it out to me before I could see it myself.

More recently, I’ve seen the same thing happening in my writing. The more I write—whether short stories, flash fiction, or essays like this—the more I notice recurring rhythms and themes. The voice sounds like me. It’s a voice cultivated, not born. Specifically, it’s a combination of the way I speak in person, the “scholarly” me who reads academic articles, and the breezy voice I used in a monthly column reviewing romance novels for the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel for about 5 ½ years. Now that I’ve been using ChatGPT regularly, I suppose my writer’s “voice” also is picking up some of that technology’s tics, although I edit those somewhat repetitive and predictable “tells” out whenever they startle me enough in a draft revision to feel unnatural to my “true” voice.

It’s tempting to romanticize inspiration. But creative practice often works more like a conversation across time that is unexpected, layered, and sometimes quite startling.

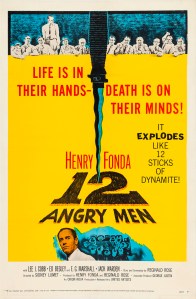

This idea, that creativity unfolds in conversation with the past, is something I first explored in graduate school—long before AI was part of the equation. My dissertation focused on plagiarism, but not in the usual “academic dishonesty” sense. I was less interested in cheating than I was in the murky, fascinating questions beneath it:

What does it mean to be original?

Where do we draw the line between influence and theft?

How do authorship and ownership work in a world where language—and culture itself—is inherently collaborative?

I found myself drawn to theories of “intertextuality,” which view creativity not as the invention of something entirely new but as the reconfiguration of what already exists. What began as an academic inquiry slowly became a creative framework, one I now bring to everything I make. That shift in perspective helped me see how meaning emerges not from a single voice in isolation—i.e., not from the notion of the “author as individual genius,” a Romantic-era idea reinforced by legal and educational systems through concepts like copyright and plagiarism—but from the dynamic interplay between texts, readers, and cultural contexts. In many ways, that intellectual grounding continues to shape how I approach my own creative practice—and how I think about the implications of AI tools in our evolving creative landscape.

Art doesn’t emerge fully formed. It borrows. It rewrites. It loops back on itself. This realization—that style emerges from layering and repetition—echoes what literary theory has long argued about how “meaning” is made. And in an era when generative AI can mimic human style, these questions about voice, originality, and authorship feel more urgent than ever.

Where Do Ideas Come From? (Hint: All Art Is a Remix)

The term intertextuality was first coined in the 1960s by Bulgarian-French theorist Julia Kristeva, building on the ideas of Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin. Kristeva’s key insight was this: No text exists in a vacuum. Every work of literature, art, or culture is shaped—consciously or unconsciously—by other works that came before it. Rather than seeing a book or a song or a film as a sealed-off creation, Kristeva urged us to view all texts as part of a vast, ongoing web of meaning, in dialogue with other texts across time and space.

In more practical terms, “intertextuality” refers to the way one work references, echoes, or engages with another. Sometimes it’s deliberate, like a line that quotes Shakespeare, or a scene that restages a famous photograph. Other times it’s more unconscious: a tone, a structure, a melody, or a plot pattern that feels familiar because we’ve encountered it somewhere before.

You can see intertextuality in nearly every form of creative work:

- In literature, James Joyce’s Ulysses mirrors the structure of Homer’s Odyssey while placing its action in modern Dublin.

- In cinema, Quentin Tarantino’s films are layered with allusions to older grindhouse, Western, and kung fu movies—not as parody, but as homage.

- In music, Beyoncé’s Lemonade draws on visual and poetic references from African American literature, history, and visual art, creating new layers of meaning through those echoes.

- In satire, intertextuality often becomes a tool for critique: think of The Simpsons or Saturday Night Live sketches riffing on politics or pop culture in real time.

These intertextual moves can take the form of allusion (a nod), homage (a tribute), pastiche (a playful or reverent mashup of styles), or satire/parody (a critical imitation). Each invites the audience to recognize and respond to prior texts, deepening the experience.

We often talk about artists’ “influences”—the books, bands, films, and thinkers who shaped their style or worldview. Influence is a helpful concept, but it can imply a one-directional flow: this artist borrowed from that one. Intertextuality goes a step further. It sees the creative process as layered, recursive, and cultural, not just personal. And it recognizes that meaning doesn’t come solely from the creator—it emerges in the interplay between texts, audiences, and contexts.

Voice, Originality, and the Echoes We Choose

Perhaps nowhere is intertextuality more apparent—and more audible—than in music. Consider Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Kurt Cobain once admitted (his term, in this Rolling Stone interview) that he was trying to write a Pixies song when he came up with it, and he was also struck by the guitar riff in Boston’s “More Than a Feeling.”

Here is Boston’s “More Than a Feeling. Listen for that guitar riff at the 43-second mark.

The video below is Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” Listen for the opening guitar riff at the very beginning and then again throughout.

Here’s how Cobain described the creative spark behind “Teen Spirit”:

I was trying to write the ultimate pop song. I was basically trying to rip off the Pixies. I have to admit it [smiles]. When I heard the Pixies for the first time, I connected with that band so heavily I should have been in that band — or at least in a Pixies cover band. We used their sense of dynamics, being soft and quiet and then loud and hard. ‘Teen Spirit’ was such a clichéd riff. It was so close to a Boston riff or ‘Louie, Louie.’ When I came up with the guitar part, Krist looked at me and said, “That is so ridiculous.” I made the band play it for an hour and a half.

Although the Pixie’s style and the “clichéd” Boston/”Louie, Louie” riff may have been influences for the creation of “Teen Spirit,” once the Nirvana song was released and it gained its own cultural text, its relationship to Boston’s earlier song became an example of intertextuality. Listeners could hear the echo, the contrast, the transformation. That interaction between songs created something new, not only because of what Cobain was doing but also because of what the audience beyond was hearing and interpreting.

In this way, intertextuality reminds us that creativity is not about pure originality—it’s about participation. Every act of creation joins a lineage. That’s not limiting; it’s liberating. It’s not a constraint—it’s a chorus you get to join. It means we’re always part of something larger.

In A Moveable Feast, the 1963 memoir of his time in 1920s Paris, Ernest Hemingway talks about how he would go to the museum every afternoon after he had finished his writing for the day:

I was learning something from the painting of Cézanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have dimensions that I was trying to put in them. I was learning very much from him but I was not articulate enough to explain it to anyone.

Although Hemingway wasn’t painting, he was in dialogue with Cézanne’s aesthetic of dimension through omission, presence through absence. The result? Stories that spoke volumes by what they left unsaid. In “Hills Like White Elephants,” for example, the woman is pregnant. An abortion looms. But none of this is stated outright. The story asks readers to fill in the blanks—to sense the depth behind the surface. Hemingway’s writing wasn’t a mirror of Cézanne’s art, but an echo of it—an intertextual response across form. This, too, is intertextuality—not copying, but letting one medium inform another in pursuit of deeper meaning.

Like Hemingway, the famed mid-twentieth-century painter Grandma Moses also created in a language others had already spoken—only hers was visual. A self-taught “outsider” artist who took up painting in her late 70s, she brought with her decades of embroidery experience, and it showed in the stitchlike brushwork she used to render grass, trees, and the colorful textures of rural life. Her work was not naive, but deeply intertextual—her painting rooted in visual language shaped by a very different medium, embroidery.

Grandma Moses’ story reminds us that creative style often emerges less from conscious invention and more from a combination of circumstance and accumulated experience—a dialogue between context, media/mediums, materials, and memory. No creative act exists in isolation, which is exactly why the rise of generative AI poses such provocative questions.

When we talk about AI-generated text or art, perhaps the question shouldn’t be “Is it original?” Instead it might be “What lineage, or what thread of conversation, is it participating in?” Intertextuality offers a richer lens for thinking about authorship—especially as generative AI enters the mix as a creative tool. Is ChatGPT merely a “plagiarism machine,” as linguist Noam Chomsky argued in a New York Times op-ed (March 8, 2023)? Or is it something else—more like an amplifier or portal, refining and rerouting the threads of these intertextual conversations? Perhaps whether AI degrades creativity or extends it depends not on the tool, but on the intent and awareness of the person using it.

(Then again, as Marshall McLuhan famously stated, “the medium is the message”—meaning that the tool itself is the message, not the intent and awareness of the person using it. That’s a different discussion—one I’ll save for another post.)

Why This “Creative Practice” Series? Why Now?

I’ve been writing occasionally about AI on my blog for the past year. But I realized that this particular thread—AI and the creative process—needed a dedicated home. A place to reflect more deeply, share experiments, and connect with others who are also wondering what it means to be creative in this strange new landscape.

That’s what this series on “Creative Practice in the Age of AI” is for.

Whether you’re a teacher, artist, writer, skeptic, or simply curious—if you care about creativity and you’re paying attention to what’s changing, you are very welcome here.

Every other week (most of the time), I’ll share either 1) an essay about creative practice and its evolving terrain, or 2) a piece of my own original creative work that emerged from collaboration with AI—along with my behind-the-scenes insights, including the “chat,” on how it came together.

These posts aren’t polished, final “declarations” but rather explorations in progress. They’re snapshots of ongoing discovery—artifacts of the questions I’m living with.

And maybe you are, too?

If so, I’d be honored to have you along.

Who Am I?

I’m Katherine Wikoff, a writer, photographer, and professor of humanities at Milwaukee School of Engineering, where I teach courses in digital culture, communication, and creative expression. I have a PhD in English with a focus on rhetoric and composition, and over the years, my work has spanned everything from political essays and film studies to fiction and photography.

I’ve always been interested in how meaning gets made—how people use language, imagery, and story to understand the world and shape their place in it. That’s what led me to study authorship and plagiarism in graduate school. My dissertation, The Problematics of Plagiarism, asked questions we’re now grappling with in real time: What does it mean to create something “original”? Where do we draw the line between influence and theft? Who gets to be called an author? And, perhaps even more importantly: Who decides?

In the Age of AI, You Are Still the Driver

Generative tools can help with process. They can even be collaborative, even inspiring. But they can’t do the practice part for you. The connecting. The choosing. The listening. The looping.

Creative practice is how you find your rhythm. It’s how you teach yourself what matters, what you’re good at, what you want to say. If you’re experimenting with AI tools, that’s still true—maybe more than ever. A chatbot can’t tell you where your story begins. But practice can.

Just start. That’s where everything begins.

And even with all the “influence” and “intertextuality” in play, your art remains both “original” and entirely your own. The words may previously have been spoken, the colors mixed, the chords struck, the steps danced—but never in quite your way. Not with your hands. Not through your voice.

This Week’s Suggested Creative Practice

Your Intertextual Self: The Artist You’ve Been and the One You’re Becoming

Every post in this “Creative Practice in the Age of AI” series includes a “creative invitation,” a list of small (but hopefully meaningful) exercises you can try on your own terms. This week’s exercises are intended to prompt reflections on your growth as a writer, teacher, artist. How has your creative practice taken shape? What are your influences? What other writers or artists have “spoken” to you through their work? And finally, what style or creative vision seems to characterize your work?

1. The Practice Timeline Look back at the last 10 years (or 5, or 15—your choice). What’s something creative you’ve done regularly—even if it didn’t feel “important” at the time? It could be journaling, taking photos on walks, collecting quotes, designing flyers, tinkering with recipes. Now draw a timeline. Mark moments of growth, shift, or surprise. What emerged over time? Can you see a pattern? A style? A voice?

2. The Influence Inventory Think about this question: What shaped you as a creative person? Make two lists:

Your creative influences: authors, artists, thinkers, places, objects, movies.

Your creative “un-originals”: things you borrowed, mimicked, or remixed.

Then reflect on this question: Where do originality and influence blur for you?

3. The Practice Spiral Creativity isn’t linear. It spirals. Write about something you keep coming back to—an image, a story idea, a question, a problem. What keeps circling back into your work or life? Is it time to move past it—or move deeper in?

Thank you for reading this week’s post, and I hope to see you again next time!