I haven’t written a “political analysis” type of post in a long time. But I just finished teaching a political science course, and because I created several new slides this past term to talk about the (sadly) still-continuing conflict between Russia and Ukraine, I thought I’d share some of them with you.

I’ve written about Russia and Ukraine before, a few times actually. Here’s the first one (and the one that I’m building off of in today’s post): https://katherinewikoff.com/2014/03/10/the-russia-ukraine-syria-connection-and-why-turkey-may-be-in-crisis-next/

This will be an image-heavy post, because I’m basically just uploading my slides and telling you about them. I thought about doing a video of me walking through the slideshow, but decided against that because, ironically, it would probably take more time to create a decent video than it would to upload slides and add a few lines of explanation.

So here goes.

First, here’s that map of Russia I posted 11 years ago.

Public domain. From “The World Factbook,” U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rs.html)

Public domain. From “The World Factbook,” U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rs.html)[Aside: The CIA’s “World Factbook” is an excellent resource for anyone interested in geopolitics. And, in fact, you can buy the current edition on Amazon, $25 for the paperback.]

As I said in that March 2014 post (shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine the first time), Russia is a vast country that is virtually landlocked. The most populous areas have limited access to ports, and the huge northern coastline is inside the Arctic Circle.

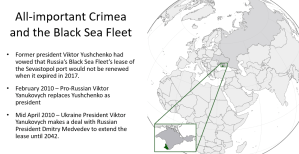

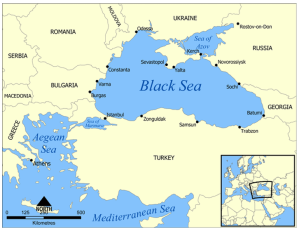

Let’s turn briefly to Russia’s navy. Russia has a very important naval base at Sevastopol, which is located on the Crimean Peninsula in the Black Sea.

The map above does a nice job of putting Crimea into the larger geographical context, plus it shows you (in dark green) where Sevastopol is.

As the slide above also mentions, Russia’s lease on Sevastopol was set to expire in 2017, and Ukraine’s President Viktor Yushchenko had warned that Russia’s lease would not be renewed.

You may remember Viktor Yushchenko as the Ukrainian president who was not a fan of Russian influence over his country and who was mysteriously poisoned during his campaign for the presidency in 2004.

Here is Yushchenko before being poisoned.

By European People’s Party – File:Flickr – europeanpeoplesparty – EPP Congress Brussels 4-5 February 2004 (8).jpg, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=103506724

By European People’s Party – File:Flickr – europeanpeoplesparty – EPP Congress Brussels 4-5 February 2004 (8).jpg, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=103506724Here he is after.

By Muumi – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=851855

By Muumi – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=851855Expert toxicologists have said that the abnormalities in Yushchenko’s face (for example, the thickened, pockmarked skin) are due to chloracne, which results from dioxin poisoning. Yushchenko’s blood was found to have dioxin levels 6,000 times above normal. [Aside: Have you noticed how often people who criticize Russian President Vladimir Putin end up getting poisoned? Just saying.]

So anyway, Yushchenko did live and he did win the election. Things weren’t looking good for Russia in terms of keeping its lease on the Sevastopol naval base.

Then in February 2010 a pro-Russia president, Viktor Yanukovych, replaced Yushchenko. By April 2010, just two months after Yanukovych was elected, Russia had its new lease, good through 2042.

Here’s what happened in Ukraine’s parliament when votes were counted to see whether Russia’s lease at Sevastopol should be renewed.

As you can see, there were very strong feelings on both sides, pro-Russian-lease and anti-Russian-lease.

Protests began against President Yanukovych immediately, and he was, as Wikipedia says:

removed from the presidency in the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, which followed months of protests against him. Since then, he has lived in exile in Russia.

Yanukovych fled Ukraine, essentially in the dead of night, after Ukraine’s parliament voted unanimously to reinstate the Constitution of 2004, putting some limits on Yanukovych’s power and in a practical sense issuing a direct “no confidence” vote—in other words, a rebuke—from the parliament.

Without going down the rabbit hole too much here, prior to these events Ukraine had also been starting to lean toward establishing a formal trade relationship with the European Union, and Yanukovych had even seemed supportive of that. But then Russia got worried and began pressuring him to back away. Russia began a trade war, restricting Ukrainian imports, and who knows what other kind of pressure was applied. Anyway, all of a sudden Yanukovych pulled out of the expected agreement with the European Union, which the Ukranian people weren’t happy with, sparking increased protests.

Immediately after Yanukovych was “removed” from Ukraine’s presidency, Russia invaded. Retaliation? An effort to cut their losses? Here’s a remarkably succinct summary of the Russia-Ukraine War from Wikipedia, with all the broad-brush details in clear focus (I copied and pasted straight from Wikipedia, so you can link straight over to their references if you want):

The Russo-Ukrainian War began in February 2014. Following Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity, Russia occupied and annexed Crimea from Ukraine. It then supported Russian paramilitaries who began a war in the eastern Donbas region against Ukraine’s military. In 2018, Ukraine declared the region to be occupied by Russia.[8] These first eight years of conflict also included naval incidents and cyberwarfare. In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and began occupying more of the country, starting the biggest conflict in Europe since World War II.

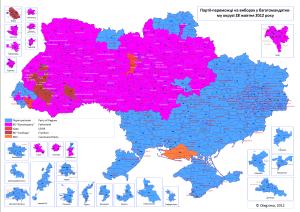

In fairness to Russia’s claim that the people of eastern Ukraine are ethnically and liguistically Russian and therefore welcome Russia’s presence, here is a 2012 electoral map showing that eastern Ukraine did in fact cast their votes in support of the pro-Russian candidate Yanukovych.

By Olegzima – Own work http://www.cvk.gov.ua/vnd2012/wp001.html#, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22450540

By Olegzima – Own work http://www.cvk.gov.ua/vnd2012/wp001.html#, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22450540But back to the main point of today’s post. The key to understanding Russia’s intentions and motivations in this war can be discerned from maps, in my opinion. Crimea is an especially crucial pain point. But even there, Crimea is only part of the story.

So, let’s begin by redirecting our attention back to Crimea and proceed from there.

First, Crimea has been important before. Did you ever study “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” by Alfred, Lord Tennyson in a literature class? Here are some excerpts you might recognize (see the entire poem at the Poetry Foundation’s website HERE):

Half a league, half a league,Half a league onward,All in the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.“Forward, the Light Brigade!Charge for the guns!” he said.Into the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.

And although the soldiers know someone has “blundered” and their charge is doomed . . .

Theirs not to make reply,Theirs not to reason why,Theirs but to do and die.Into the valley of DeathRode the six hundred.

Fewer than one-third of the “six hundred” survived. That famous, ill-fated charge occurred during the Crimean War of the 1850s, between Russia and the declining Ottoman Empire, the United Kingdom and France. Mostly that war was fought to curb Russia’s imperial westward ambitions and to help the Ottoman Empire (aka, mostly Turkey) hold out against those ambitions. Speaking of which . . .

Oh! Another map 🙂

By The British Library – Image taken from page 27 of ‘The Illustrated History of the War against Russia. Plates’, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66108914

By The British Library – Image taken from page 27 of ‘The Illustrated History of the War against Russia. Plates’, No restrictions, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=66108914Although the Ottoman Empire (weakened but victorious) maintained control of Crimea and the Black Sea coastline following the Crimean War of “Light Brigade” fame, Russia gained control in the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). The map’s green areas show places that the Ottoman Empire ceded to Russia from Turkey

So anyway, back to the present day. Here’s a map that shows the Crimean Peninsula, its position on the Black Sea, and its orientation to both Russia and Ukraine more clearly. Crimea is the big diamond-shaped area of yellow inside the Black Sea, and you can see by the fact that it’s kind of dangling off the Ukrainian mainland that it is, indeed, a peninsula.

By Created by User:NormanEinstein – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=239407

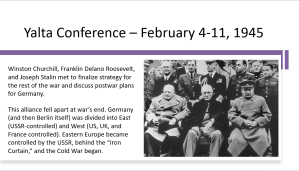

By Created by User:NormanEinstein – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=239407If you look closely at Crimea on this map, not only can you see Sevastopol just around the bottom corner of the peninsula to the left, but on the right you can also see Yalta. Remember this famous photo of FDR, Churchill, and Stalin (Allied powers) at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, as World War II was nearing its end?

Sorry to share that if you already knew all about Crimea, but I grew up knowing that Yalta photo but having zero context for what and where “Yalta” was, so I thought it was interesting.

So we’ve already established Russia’s long history with Crimea, including its fight over the territory with Turkey (aka, the Ottoman Empire). As the map above shows, there’s only one way for ships to get out of the Black Sea to the Aegean Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the Atlantic Ocean, and the whole rest of the world.

Through Turkey. Right through the middle.

Russia exports a lot of oil to the rest of the world in tankers through the Turkish Straits from its Black Sea port city of Novorossiysk, which you can see on the map above due east of Sevastopol and Yalta, across the water to the Russian mainland.

Here’s another map, showing a close-up view of the passageway through the Turkish Straits, from the Black Sea entrance at the Strait of Bosphorus (also spelled Bosporus), shown in red, cutting through Istanbul, all the way to the Dardenelles, shown in yellow, at the other end, where it opens into the Aegean Sea.

User:Interiot, CC BY-SA 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5>, via Wikimedia Commons

User:Interiot, CC BY-SA 2.5 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5>, via Wikimedia CommonsTurkey has pledged that the Turkish Straits will remain open to international maritime traffic, even though the area lies within Turkey’s territorial waters (From Wikipedia):

The modern treaty controlling access is the 1936 Montreux Convention Regarding the Regime of the Straits, which remains in force as of 2025. This Convention mandates that Republic of Turkey allow the free passage of all civilian vessels in peacetime, and requires Turkey to allow warships of some nations to traverse the straits in peacetime, but only under strict conditions – restrictions on number, size, length of stay if entering the Black Sea (if not a Black Sea power), advance notification to Turkey, and other conditions.

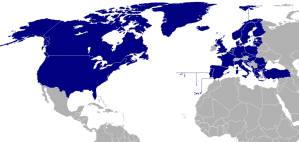

Turkey, you may recall, is a member of NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), a surviving artifact of the Cold War era that in no way resembles a relic and is, in fact, stronger than ever.

Lately NATO has been weighing heavily on Russia’s mind and looming large as a threat. (My opinion, of course, but I also think it’s pretty close to a fact.)

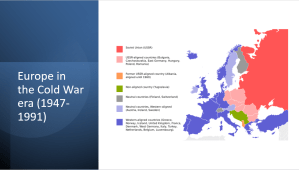

First, here is a map of Russia (when it was part of the USSR) during the Cold War.

This is a screenshot of my slide, and the image came from Wikipedia. If the words are too blurry for you to read easily on your screen, you can click on my slide to make the text clear. Even if you don’t feel like clicking to see the words, you can still get the important info from this slide just from the colors alone.

The old USSR is in red. NATO countries are in blue. You can see the old Warsaw Pact Eastern European bloc in pink. Those were all the countries like Poland and Hungary that the USSR invaded after World War II. The term “Iron Curtain” referred to the opaque “veil” that separated these countries from the rest of Europe during that period. Winston Churchill coined the term in a 1946 speech:

From Stettin in the Baltic, to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent

Thanks to the Eastern Bloc (aligned with the USSR, in pink) and Finland (neutral and officially “non-aligned,” seen in gray, sharing its long border with the USSR), the Soviet Union (mostly Russia, for our discussion) had a substantial “buffer” in place to shield it from NATO.

And then Lech Wałęsa and the Solidarity movement happened in Poland in the early 1980s. Soon Communist governments across Eastern Europe were being overturned. The Berlin Wall fell in 1989. And then finally, the Soviet Union itself fell apart and was dissolved in 1991.

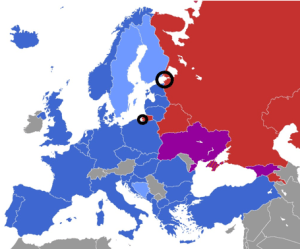

So now Russia finds itself in an interesting situation. The Cold War was sort of a standoff between NATO and the Warsaw Pact countries. The Warsaw Pact is gone. Yet NATO is stronger than ever. And getting stronger. This map shows current NATO membership.

The image was originally made by User:Donarreiskoffer. This version (corrected regarding Northern Ireland) is identical (except the size) to one uploaded by en:User:Mrowlinson which didn’t have a copyright license., CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

The image was originally made by User:Donarreiskoffer. This version (corrected regarding Northern Ireland) is identical (except the size) to one uploaded by en:User:Mrowlinson which didn’t have a copyright license., CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia CommonsHere’s a link to a really cool animated Wikipedia map that shows the growth of NATO year by year: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:History_of_NATO_enlargement_animation.gif

As you can see from the NATO map above, all the old “buffering” states are gone. Aligned Eastern Europe, gone. Neutral, non-aligned Finland, gone. With the exception of Belarus, all the old Europe-adjacent USSR states surrounding Russia are also gone.

Ukraine is trying to be gone.

And Georgia . . .

Well, Georgia is also kind of gone. And in some ways is adding a lot of pressure and urgency to the Russia-Ukraine situation (from Russia’s perspective, anyway).

If you look at this map, you can see Georgia on the far lower-right side of the Black Sea. Georgia joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (a now-defunct “hand of friendship” discussion forum for former Warsaw Pact members founded by NATO after the breakup of the Soviet Union) in 1992, one year after it became an independent state following the dissolution of the USSR.

NATO says this about Georgia:

Georgia is one of NATO’s closest partners. It aspires to join the Alliance. Over time, a broad range of practical cooperation has developed between NATO and Georgia, supporting Georgia’s reform efforts and its goal of eventual NATO membership. The country contributes to the NATO-led Operation Sea Guardian and cooperates with the Allies and other partner countries in many other areas.

In April 2008, NATO allies agreed that Georgia could become a NATO member, provided it meets all necessary requirements, a decision that has been reconfirmed at successive NATO summits.

In August 2008, just four months later, guess who invaded Georgia? And still has troops stationed there?

Russia. (Do I even need to say it at this point in the post?)

You can kind of see Russia’s reasoning. If you look at the above map, you can see that the Black Sea is rimmed by Turkey, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, and Georgia. Three of those countries are NATO members. One (Georgia) has ties to NATO and is pre-approved to join whenever it wants to and meets the requirements for membership. And one (Ukraine), even though it has no ties to NATO and has not expressed any official interest in joining NATO, has ties to the European Union, has expressed interest in EU membership, and in fact is now an official candidate for membership.

Here’s another look at that NATO map. (Actually this map is a bit older, as Sweden and Finland hadn’t yet become full members, but it’s from a slide I made a couple years ago to highlight two Russian port cities, and I don’t feel like making a new one today just to have the most up-to-date version of NATO’s membership represented. The pertinent points are still accurate.)

In this map, the two purple countries are Ukraine and Georgia, and you can see at a glance the amount of blue and purple surrounding the Black Sea compared with red. But check out the two areas circled in black. These are two Russian port cities. The larger circle is the better known: St. Petersburg. Today both Sweden and Finland are full NATO members. So you can see that for ships to get into and out of St. Petersburg, they kind of have to sail through a gauntlet of NATO nations, similar to the situation encountered in getting out of the Black Sea through Turkey. All well and good in times of peace, but not exactly safe and convenient should a state of war exist between Russia and NATO nations.

The other, smaller circle is the port city of Kaliningrad. I don’t know how well you can see it on this image as my circle does a fair job of obliterating the area below it, but Kaliningrad Oblast, of which Kaliningrad is the largest city, is isolated from the rest of Russia. It’s an “enclave” completely surrounded by, you guessed it, NATO countries.

Apart from Murmansk, which you can see way at the top left of Russia in the first map of this post, these are the only two Russian ports in Europe with access to the Atlantic Ocean. Murmansk, although an ice-free harbor, lies inside the Arctic Circle and requires a bit of a northerly jog to reach, sailing up and around Norway, Sweden, and Finland. In its favor, though, Murmansk is the only port in Russia with unrestricted access to the Atlantic. Everything else requires some degree of acquiescence from the NATO countries that surround/enclose their sea access.

Back to Russia and Ukraine. Remember the title of this blog post? It has been so long ago now since you started reading, LOL, so here it is:

“Pragmatism vs. Idealism (Or, what to do about Russia and Ukraine?)”

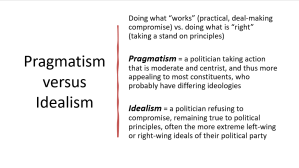

“Pragmatism” and “idealism” are some basic political-science vocabulary words that I want my students to learn. Here’s a slide that defines them.

We also spend a fair amount of time talking about “ideology” in my political science class, because I think it’s crucial to understand that human beings are extremely complex and have vastly different values and ways of perceiving and acting in the world. “Pragmatism” and “idealism” are similar to “ideology” in that some people lean toward pragmatism, while others lean toward idealism. The extremes on both sides perceive the world through their highly different lenses and have great difficulty comprehending, much less respecting, how someone else could see things a different way.

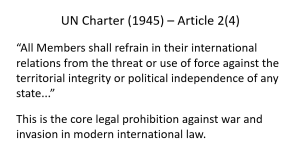

In the case of the Russia-Ukraine War, an “idealistic” take on the situation would be that Russia is in the wrong and cannot be allowed to get away with invading and unilaterally annexing the territory of another sovereign state. The United Nations charter is quite clear about behavior like this.

It’s hard to imagine a more idealistic institution than the United Nations. International politics is kind of like the Wild West. The UN as a world governing body has nowhere near the sovereignty of a state. The UN cannot force a sovereign nation to do something it doesn’t want to do. And every state on earth is “sovereign.”

One widely accepted definition of a “state” among political scientists, in fact, is that a state is an entity holding a monopoly on violence over a geographical area. From the Wikipedia article on “Monopoly on Violence“:

In political philosophy, a monopoly on violence or monopoly on the legal use of force is the property of a polity that is the only entity in its jurisdiction to legitimately use force, and thus the supreme authority of that area.

And

[ Late 19th- and early 20th-century German sociologist, historian, jurist, and political economist, Max] Weber, claims that the state is the “only human Gemeinschaft which lays claim to the monopoly on the legitimate use of physical force. As such, states can resort to coercive means such as incarceration, expropriation, humiliation, and death threats to obtain the population’s compliance with its rule and thus maintain order. However, this monopoly is limited to a certain geographical area, and in fact this limitation to a particular area is one of the things that defines a state.”[2] In other words, Weber describes the state as any organization that succeeds in holding the exclusive right to use, threaten, or authorize physical force against residents of its territory. Such a monopoly, according to Weber, must occur via a process of legitimation.

An “idealistic” solution would involve application of the “international law” in this situation to force Russia to leave Ukrainian soil. But the United Nations does not have the monopoly on violence that a state does. It does not have a police force, it cannot arrest a country’s leaders and put them on trial, convict them of a crime, and sentence them to prison or even death.

Yes, there is the International Court of Justice, but a state is not bound to comply with its decisions. The United States, in fact, withdrew from the ICJ’s “compulsory jurisdiction” under President Ronald Reagan in 1986. We view ICJ rulings as “advisory” now. And the ICJ has no authority to enforce its rulings.

There is also the International Criminal Court, a far more recent arrival on the scene (2002). It has the jurisdiction to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, etc. But like the ICJ, the ICC has limited power to enforce its rulings, and several countries have already “opted out,” as it were.

[NOTE – Additionally, as of today the ICC’s chief prosecutor, Karim Ahmad Khan, has reportedly decided to go on leave while allegations of sexual misconduct, apparently in the form of coerced sexual intercourse with a staff member on multiple occasions over a period of months, are investigated, which is bad enough, but there are also allegations that he may have charged Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu with war crimes associated with Gaza partly in order to discourage his accuser from coming forward, as she was reluctant to do anything that might derail the war crimes investigation, and partly to gain support from anti-Israel countries in case she came forward anyway. If these allegations are true, they will foster mistrust in the moral authority of the ICC and damage the legitimacy of its role in adminstering international justice.]

So in some ways, the United Nations is a nice idea but one that may also ultimately prove to be as ineffective as its predecessor, the League of Nations, in achieving its mission of maintaining world peace.

Yet, at the moment, it’s all we’ve got. And ironically, although it’s technically against UN rules, several UN member states are applying severe sanctions against Russia. If nothing else, the presence of the UN has allowed for immediate, transparent, and ongoing cooperation among these states to impose a punishment that the official body cannot, especially given Russia’s position as a permanent, veto-wielding member of the Security Council.

An “idealistic” solution would require returning Ukraine to its pre-invasion status and also “punishing” Russia in some manner for its transgression. If Russia “wins” by getting to keep the territory it has invaded while also getting to enjoy full membership status in the United Nations (including a permanent seat on the Security Council), then the UN charter is worthless and the member states are hypocrites. Russia cannot keep Crimea or eastern Ukraine.

However . . .

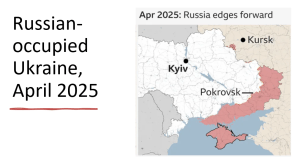

As the map above shows (slide’s original image source is the Institute for the Study of War, via the Visual Journalism team at BBC News), the area of Ukraine currently occupied by Russia is like a “freeway” strip of land leading straight down from Russia to Crimea and Sevastopol. You may also remember that map earlier in this post showing election results from the 2010 Ukraine presidential race, in which the pro-Russia candidate captured this narrow strip plus even more of eastern Ukraine. So the area currently occupied by Russia isn’t as anti-Russian as western Ukraine is.

“Pragmatism” means looking at things the way they are instead of the way that they should be. Pragmatically and realistically, it’s easy to see that Russia will NEVER give up Crimea voluntarily, nor will Russia give up the land route to reach it. Especially when you consider the centuries of bloody history behind acquiring this piece of land and its strategic importance today for Russia’s military and economic viability.

Furthermore, check out this slide.

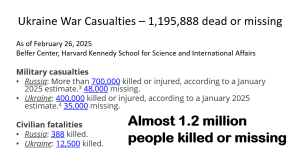

A “pragmatic” solution would look at this death toll and seek to “make a deal” to end the ongoing conflict. Making a deal most likely means, pragmatically and in actual fact, finding a win-win solution that both parties can live with, even though both parties may not get everything they want and feel they rightly deserve. A “win-win” solution will probably not be “right” in terms of international law and an idealistic view of right and wrong. A pragmatic solution will leave many people unhappy, even though it may be the only way to reach a negotiated solution.

Idealism in many ways precludes negotiation. For example, protestors occupying college campus buildings during the late 1960s and early 1970s often issued “non-negotiable demands” as their terms for ending the situation. And there is also the general rule against negotiating with terrorists, both because it is wrong and because it changes the rules by incentivizing future terrorism as an effective tactic. Such an idealistic stance stands in total contrast with the very tangible, immediate, and pragmatic reality of negotiating with these terrorists in this specific situation and getting a hostage released today.

In the end, the question of what to do with Russia and Ukraine depends on which approach, pragmatic/realistic or idealistic/principled, ends up in the driver’s seat.

One “condition” for peace on Russia’s part that I’ve heard mentioned (in other words, one of Russia’s “non-negotiable demands”) is that Ukraine can never be allowed to join NATO. In this post I’ve shown a lot of maps and talked a lot about NATO. Suppose the war ends with Russia somehow keeping the territory it has taken over and seeing to it that Ukraine is barred from ever joining NATO.

The question for an idealist might be: Is that fair or right?

The question for a pragmatist might be: Would it produce a truly lasting peace?

I, of course, don’t have an answer.

In fact, the main thing I came here to say is that no one really has THE answer. Someone who values principles over pragmatism will see the situation in terms of right and wrong, good versus evil. And someone who values pragmatism over ideals will see the situation in terms of achievable reality versus lofty, unreasonable, and unrealizable expectations.

Oh dear! I just saw how long this post is: over 4,000 words! Like, 13 times the length of many of my posts where I just share a photo and talk about it. But I guess 4,000 words is what it takes, in my opinion, to talk about political situations.

If I were to talk about Israel and Gaza, who knows how many words I’d require! Like, a book could be written and not do justice to the complexity.

But despite the complexity and our limited access to all the facts, we do seem to have plenty of opinions about conflicts in places like Israel and Gaza, Russia and Ukraine, and every other troubled spot on earth. Our somewhat under-informed opinions aren’t “bad” or “insubstantial,” but they probably aren’t “right” or “wrong,” either.

Now that I think of it, I don’t like hearing statements like, “If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,” or “If you’re not outraged, you haven’t been paying attention.” It bothers me when people pile on the hate because someone expresses (or even holds) an opinion other than their own or the current social consensus.

We saw it during the COVID-19 pandemic with mask wearing (or not, or incorrectly), outdoor gatherings (protesting lockdowns versus protesting police violence), and vaccination (or not). As our knowledge changed or as we sensed social pressures changing, public opinion fluctuated wildly and angrily. Opinions expressed via words or actions were assigned moral weight, and both personal and societal relationships were fractured as a result.

Each of us has a strongly established internal value system, a permanent, fairly unalterable lens through which we see the world. Maybe saying this reveals me to be a pragmatist? I’m not a relativist, and I don’t think I lack an ability to discern and judge among myriad points of view and articulations of reality. But I also don’t see the world in black-and-white terms or feel any certainty that I have the “right” answer. I don’t think anyone has that.

But who knows? Maybe I’m wrong. 🙂

If there’s one thing I feel certain of, though, it’s that I wish we could more readily acknowledge the humanity and “divine spark” (in a “namaste” sense) of others. We are all separate beings, individuals with diverse characteristics, experiences, and values, yet we are also all part of a singular human “spirit,” sharing a common human identity and existential interconnectedness.

Evil exists. And not just in terms of “good” people and “evil” people. The potential for evil exists inside all of us (I believe), and even “good” people are capable of monstrous acts.

But on the flip side, goodness also exists. People who have different worldviews and values and opinions can be good people, who want good outcomes. It would be so nice if that automatic leap to judgment and anger could more frequently be set aside in favor of assuming good intentions, or at least not bad intentions, as the underlying motivation of people we perceive as doing “bad’ things.

Or at least in favor of trying to understand other people’s ways of seeing the world.

[Aside: This post is now over 4,800 words. Plus, I can feel myself getting preachy, a sad tendency of mine that I try hard to avoid, so it’s time to wrap things up and call it a day. Thank you so much for reading if you’ve gotten this far!❤️]

I didn’t know much of this history. Thanks! Also, I love the Charge of the Light Brigade. I used to quote the “theirs not to make reply, theirs not to reason why, theirs but to do and die”, especially at work! Lol

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely at work!

LikeLike